MenB update for the Jessica Bethell Foundation

Current picture of MenB and on-going research

Almost five million doses of the MenB vaccine Bexsero have been given safely to children in the UK, and last week research published in the New England Journal of Medicine confirmed that, cases of MenB in young children have reduced by 75% – meaning 277 cases of meningitis and septicaemia have been prevented.

This provides welcome evidence that the vaccine is protecting children, and that protection is sustained for at least two years.

Also published last week were the findings of the Australian ‘B Part of It’ study. This aimed to find out whether vaccinating teenagers with Bexsero could prevent them from carrying MenB bacteria in the back of their nose and throat, preventing the spread of bacteria, resulting in wider population protection (via an effect sometimes referred to as ‘herd protection’).

The findings of the research suggest that for Bexsero, protection against MenB will rely on direct, individual protection, as the vaccine does not appear to have an effect on the carriage of bacteria. In late 2018, South Australia introduced routine MenB vaccination for babies and teenagers, and this will provide the ideal opportunity to further evaluate the impact of Bexsero using real world experience.Although the finding that Bexsero does not appear to prevent the carriage and spread of MenB bacteria was disappointing, we are now in the position to pursue a number of alternative research avenues, which offer the opportunity to further investigate how protection can be maximised against MenB.

Now with the generous support of The Jessica Bethell Foundation, MRF are funding research to find out whether giving a single dose of MenB vaccine to teenagers previously vaccinated as infants could boost their immunity, and protect them against MenB disease through this next ‘high risk’ period. The team are currently working to analyse the levels of antibody in the blood samples collected, and the results are anticipated to become available in April 2020.

If the MenB vaccine had additional benefits, that would improve the cost-effectiveness argument for offering it to teenagers. In fact there is evidence of some level of protection against gonorrhoea – rates of gonorrhoea in teenagers in New Zealand dropped after an immunisation campaign with a precursor MenB vaccine in 2004-2006. This is possible because gonorrhoea and meningococcal bacteria are close cousins. The introduction of MenB vaccine for all teenagers in South Australia should clearly show if this effect is real. If MenB vaccine does protect against gonorrhoea, which is increasingly antibiotic resistant, this could lead to a re-evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of a teenage MenB programme in the UK.

The future extension of the UK MenB programme to teenagers would be a great step forward, but since Bexsero does not prevent the carriage and spread of MenB bacteria, vaccinating teenagers would not protect younger and older members of the population. We already know that the vaccine cannot protect against 100% of circulating MenB strains in the UK, so further research is needed to develop more broadly protective vaccines. Whole genome sequencing, a revolutionary technology that can transform clinical samples into meaningful data, offers the ideal opportunity to make such progress. Indeed, it was genomic approaches that led to development of first generation MenB vaccines.

Using genomics in the fight against MenB

A genome is often referred to as an individual’s ‘genetic blueprint’ as it contains the complete set of an organism’s DNA. Whole genome sequencing or genomics, refers to the process of working out the exact order (‘sequence’) of the chemical bases (A, T, C, G) that make up DNA.

The importance of genomics as a public health tool is becoming increasingly recognised. Following the success of the 100,000 genomes project, which helped 1 in 4 patients with rare diseases receive a diagnosis for the first time, in 2019, Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock outlined an ambition to sequence five million human genomes in the UK within the next five years.

But all living things, including meningitis bacteria, have a genome, and the benefits of using genomics extend far beyond sequencing human genomes. Indeed, it was genomic approaches that led to the development of the first generation MenB vaccine. In light of such benefits, MRF are now supporting the establishment of a Global Meningitis Genome Partnership (GMGP).

This ambitious initiative stemmed from the MRF-Meningococcal Genome Library (MRF-MGL), a free online resource that provides a complete genetic blue print of every sample of meningococcal bacteria known to have caused meningitis and/or septicaemia in the UK between 2010-2015. This marked a world first and has proved to be a valuable and lifesaving resource accessed by many world-leading researchers.

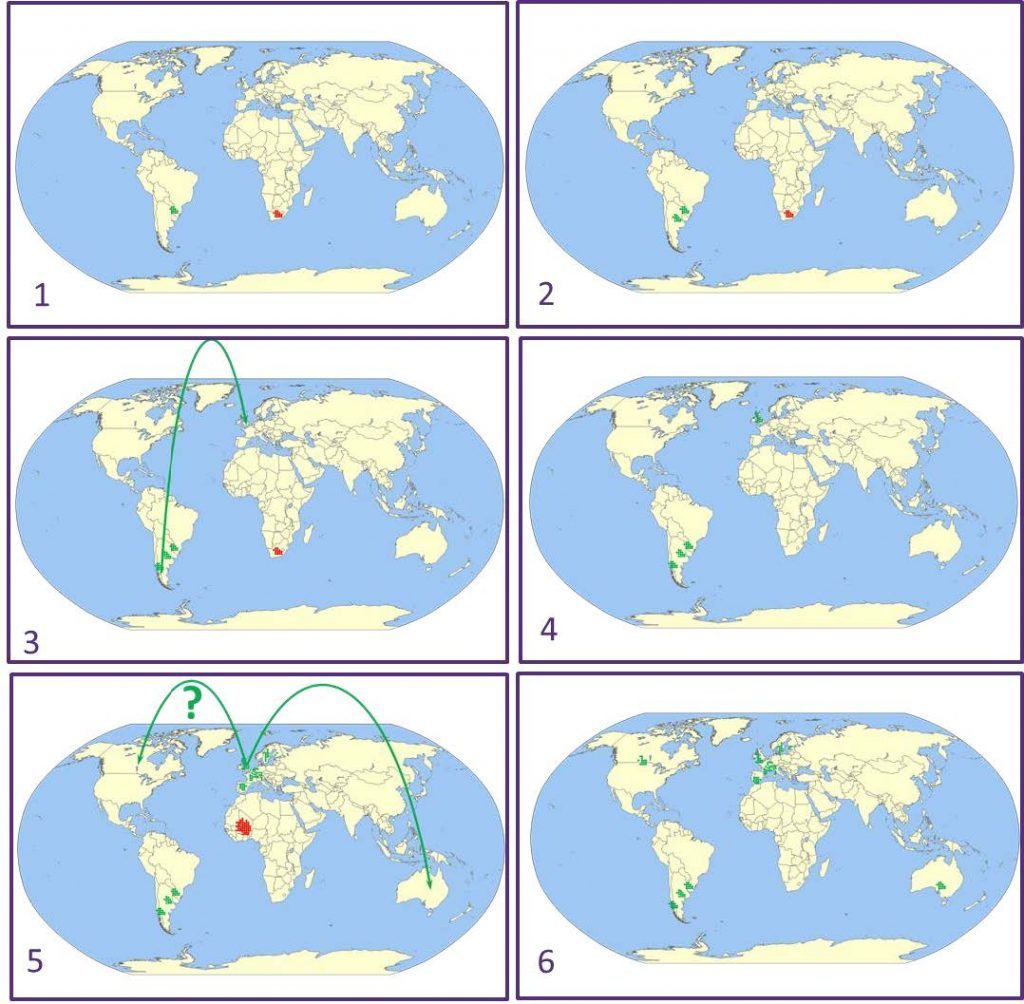

The MRF-MGL had its finest hour almost immediately, revealing that an alarming increase in deadly MenW disease seen in England and Wales in 2009, was caused by a particularly dangerous strain of MenW found to originate in South America and NOT South Africa (so called ‘Hajj strain’) as was initially expected (See Figure 1). This discovery led to the emergency introduction of MenACWY vaccine for UK teenagers to prevent further spread of this deadly disease. From 2016/2017-2018/2019 cases of MenW halved across the whole population of England. However, the predicted impact of the vaccine is far greater than this; considering that prior to the vaccine being introduced, cases of MenW were almost doubling year on year.

This demonstrates the remarkable power of high resolution genomics, as if standard approaches had been used, these strains would have appeared to be the same; delaying an appropriate public health response and resulting in more lives devastated by meningitis. This example also demonstrates the profound importance of having access to the global picture of meningitis, in tracking and responding to emerging and expanding strains of deadly bacteria.

Therefore, in recognition of the fact that meningitis is a global issue that urgently needs addressing, we are working with world-leading meningitis genome experts, to establish a Global Meningitis Genome Partnership (GMGP) that aims to establish freely accessible, representative collections of four of the leading causes of bacterial meningitis (meningococcal, pneumococcal, Hib and Group B Streptococcal).

Professor Ray Borrow, Head of the Meningococcal Reference Unit at Public Health England, whose team were also key players in the success of the MRF-MGL said:

‘Global, genomic surveillance of bacterial meningitis pathogens is essential for effective disease control; promoting reliable and prompt identification of emerging and expanding strains and supporting public health interventions. However, meningitis genome libraries currently lack global representation, missing data from countries with some of the highest meningitis burdens in the world. We are therefore delighted to be involved in the GMGP, an ambitious project, dedicated to improving our ability to track and respond to meningitis on a global scale.’

Figure 1: Emergence and spread of MenW in the UK

This series of images demonstrates how a MenW strain emerged in South America (between 2003-2008) at the same time a different MenW strain was causing disease in South Africa. In 2009 the South-American strain spread to the UK where it caused an outbreak of disease which predominantly affected previously healthy teenagers. This South American-UK strain has since continued to expand across the globe. (Diagram adapted from presentation supplied by Dr Jay Lucidarme, Public Health Manchester).

In addition to enabling the UK to keep track of and respond to emerging threats, this initiative will help the UK to maintain a successful MenB vaccination programme and facilitate development of more broadly protective MenB vaccines by identifying new and increasing strains that are causing MenB cases across the globe; and showing whether they are covered by existing vaccines. This is information that is highly sought after by vaccine developers.

Furthermore, as Bexsero is only estimated to offer protection against three quarters of MenB disease circulating in the UK, whole genome sequencing is needed to demonstrate whether cases of MenB in vaccinated individuals are true vaccine failures, or due to the disease being caused a strain not covered by current vaccines.

Obtaining a global picture of meningitis is again important, because as seen with MenW disease, as more virulent MenB strains emerge around the world, they are highly likely expand and spread, causing disease in the UK as well.